This story is about a boy who travelled from Sri Lanka to Amsterdam in the eighteenth century. He was not the only one to do this, and certainly not the most famous one. Willem lived a short life and suffered a tragic fate, though his story is worth telling, not in the least because so many elements of Sri Lankan-Dutch connections are reflected in it: from Tamil translators, community conflict, to Christian religion and Dutch revolution! The interaction of Sri Lankans and Dutchmen during the Dutch colonial period was not just contained to Asia, and to politics and economics. Over the course of 150 years, Sri Lankan people also travelled, studied and lived in the Netherlands. Around 20 of them were students of theology, trained at the Dutch seminary in Colombo, pursuing a doctorate at the universities of Leiden and Utrecht, and returning to a career in Dutch Colonial Asia. Willem, however, never left the Netherlands to return to Sri Lanka: he was buried here.

Translators and Ministers

Willem was born in Sri Lanka in 1761 as Wilhelmus Philippus Simon de Melho, in a Tamil-speaking Chettiar family. He was reportedly a keen and amiable boy. Willem’s grandfather Simon was, together with the Ondaatjes – another well-known Chettiar family – part of a clan of which many members worked for the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch Reformed Church in Sri Lanka. Within the Chettiar community they formed a faction that clashed with other members of their community, one of the reasons being Simon’s presumably low status as an illegitimate child of a formerly enslaved woman. Within the colonial government, Simon climbed the social ladder quickly though, seizing the opportunity of making himself indispensable to the Dutch as the chief Tamil translator for the VOC. His son, Philip de Melho, Willem’s father, was soon a rising star within the Dutch Reformed Church. Philip married Magdalena Ondaatje and they had several children, among whom two sons. The church considered Philip to be extremely talented and devoted. He attended the seminary, became a junior minister, and also wrote and translated several books in Tamil to explain and defend the Dutch protestant faith to his congregation in Jaffa. And while it was mandatory for all ministers within the Dutch church system to have studied theology at a university, and thus to have to travel to Europe, Philip de Melho refused. It was exceptional, especially since the Dutch governor-general had specifically arranged for him to go to the Netherlands. Was Philip scared to travel to Europe for such a long time? Was he confident enough in his own ability as a minister? Whatever his reasons were, he became one of the greatest exceptions in Dutch church history, and especially in colonial Sri Lanka, since he was even ordained as a senior minister – a predikant – without a university degree.

This map is oriented southwards, the harbour below is on the northside of the city. © Plattegrond van Amsterdam ca. 1726-1750 .RP-P-AO-20-55-3, Rijksmuseum. Anonymous artist, Reinier Ottens (I) & Josua (publisher).

To Amsterdam

Knowing that Philip de Melho had refused to go, it is at least remarkable that he did send his youngest son Willem to attend the Atheneum in Amsterdam, and after this preparatory school to continue his theology studies at university. His oldest brother had died before being able to take that trip, according to some from ‘studying too hard’, which sounds daunting, but perhaps mainly suggests he was a zealous student. It must therefore have been hard for Philip, and Willem himself, that the only remaining son was leaving the family for Europe. Fortunately, he was not alone: he travelled with his cousin Pieter Ondaatje, who was three years older and whose mother Hermina Quint was from Amsterdam. In 1773, the boys travelled to Galle first, where they boarded a ship to Amsterdam. In Galle, Pieter and Willem stayed with their aunt, whose late husband Petrus de Silva had been predikant as well. A familiar theme in this family be now, uncle Petrus himself had also studied theology in the Netherlands. On November 16th, together with several hundreds of sailors, soldiers and merchants, the boys travelled the Indian Ocean, rounded the Cape, and arrived in Amsterdam about seven months later, on 10 June 1774. There they were awaited by an unfamiliar face, but a familiar name. Pieter Quint, Pieter Ondaatje’s maternal grandfather, would be their legal guardian during their stay in the Netherlands, and the boys were to live at his house. Pieter Quint was a church elder and merchant, living in the Binnen Bantammerstraat in Amsterdam, close to the docks. This street still exists, its name refers to a region in West-Java, and this has over the centuries been a neighbourhood where many Asian travellers in Amsterdam have settled.

Of Pieter and Willem’s time in Amsterdam and attending the Atheneum Illustre not much is known. Pieter decided after four years to continue his studies in Utrecht, starting with theology, and later switching to law, resulting in doctorate degrees from both the Universities of Leiden and Utrecht. He became part of the official historical canon of the Netherlands, as one of the key ideologists and charismatic leaders of the Batavian Revolution in the Netherlands.

Archival memories

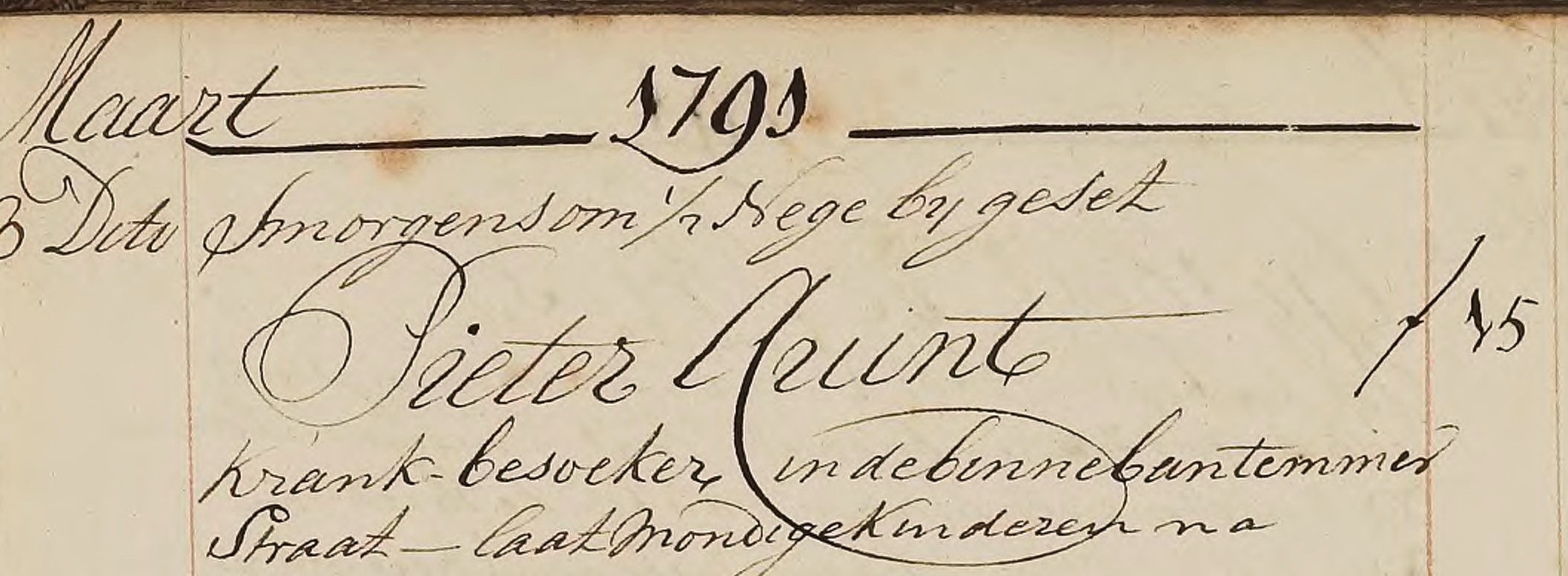

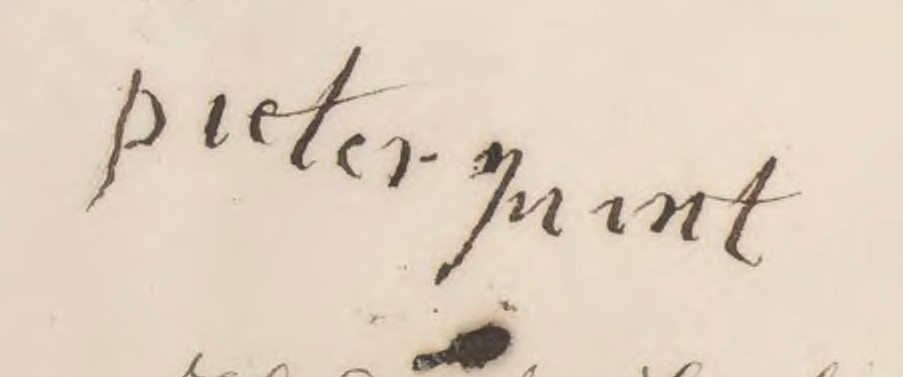

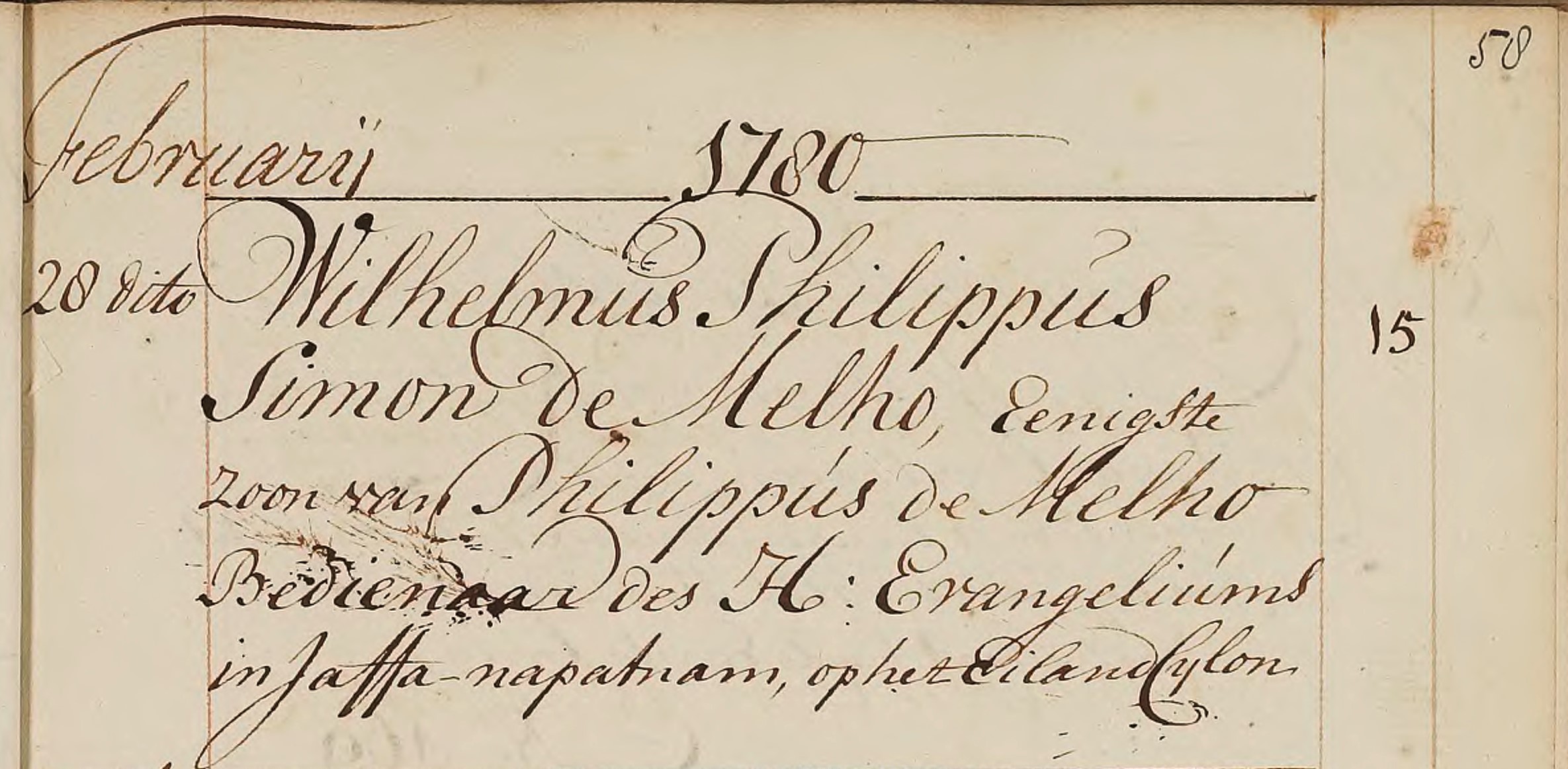

While this story might feel like it’s just getting up to steam, this is where the engine suddenly comes to a full stop. Unlike his cousin, Willem never got a degree. One of the only archival remains of Willem where he is not in the slipstream of his famous cousin or father, is his record in the Burial Registry in the Amsterdam Municipal archives. This is where I first met Willem, by reading about his death. The house at the Bantammerstraat had been struck by tuberculosis and Willem did not survive. And so, at age nineteen, not quite graduated from school and after being in the Netherlands and away from his family for seven years, Willem de Melho passed away on February 23rd 1780. The plans were ambitious, but had worked for most of his relatives: getting a degree in the Netherlands and return to Sri Lanka to work in the Reformed Church, next to his father. On February 28th, Willem was buried in the Oudezijdskapel, or St. Olof’s Chapel, at the Zeedijk, close to the harbour and the ships returning to Sri Lanka. Ten years later, Willem’s guardian Pieter Quint was also buried there. Pieter Ondaatje could not attend that funeral, as he was exiled in France. Would the death of his grandfather have reminded him of his deceased cousin? On his grandfather’s wish, and showing how much the men had meant to each other, Pieter took Quint’s name, and is nowadays remembered as Pieter Quint Ondaatje.

In the margins of his family members’ histories Willem might seem only a footnote, but in all these stories his memory does live on. On the picture below is Willem’s burial record. He is referred to as

Wilhelmus Philippus Simon de Melho, the only son of Philippus de Melho, servant of the Holy Gospel in Jaffanapatnam [Jaffna], on the island Ceylon.

It is striking, and significant for the history of Dutch colonialism and the connection with Sri Lanka, that the administrative and physical remains of these Sri Lankan men, Willem, Philip and Simon, can still be found in Dutch records and churches in Europe.

———————————————————————————————–

To read more from the world of the Ondaatje and De Melho families in Sri Lanka during the Dutch period, read Herman Tieken’s Between Colombo and the Cape. Letters in Tamil, Dutch and Sinhala, Sent to Nicolaas Ondaatje from Ceylon, Exile at the Cape of Good Hope (1728-1737). Delhi: Manohar 2015.