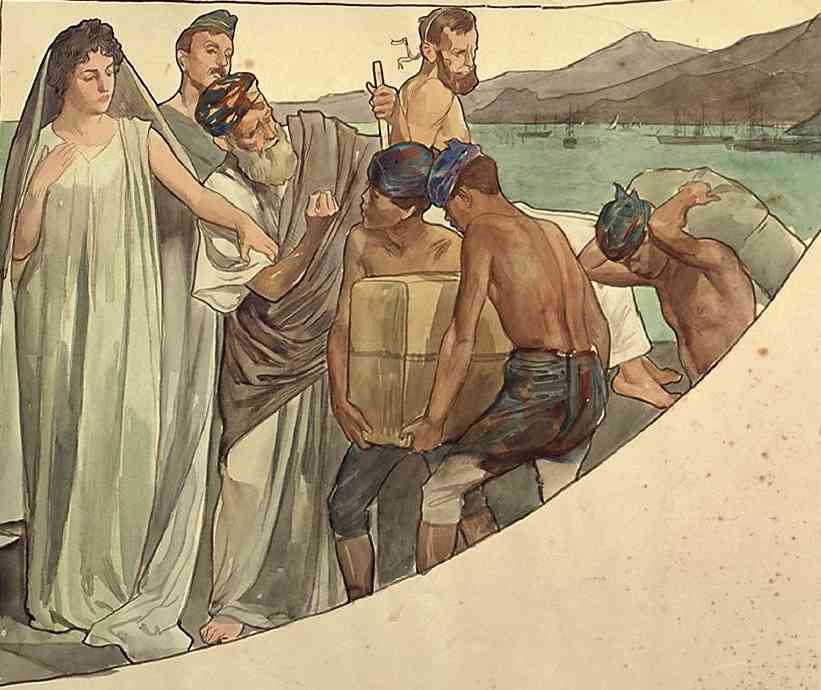

Is the white man with the beard about to assault the brown man, who seems to look utterly confused? Is the woman who seems to be restraining the white man his wife? Or is she the virgin? Who can say! This is a segment of the right panel of the widely debated ‘golden coach’, which is now being exhibited at the Amsterdam Museum. This is a segment in the controversial panel “Hulde der Koloniën” (‘a homage to the colonies’) made by Nicolaas van der Waay in 1898. Thus far the centre and left part of the panel used in the golden coach are described in the media, with the ‘Virgin of the Netherlands’ taking centre position.

I must confess that I have not dug deeper into figuring out what I am seeing in this section of the panel. But I can certainly invite any person who is reading our present newsletter, touching on the topic of ‘slavery’, to drop us a line explaining what we are seeing. It could be valuable to our audience and we shall post this on our website.

Few would dispute the fact that ‘slavery’ has been around for thousands of years, is still with us and will certainly remain in the years to come. To ask the question “what exactly is slavery?” is to impose on the inquirer the obligation, amongst other things, to consider the social relations and the concepts that govern these relations. We may consider invoking concepts such as Freedom, Justice, Equality and even should not shy away from posing the question, what is a good life? I am aware that these are subjects far beyond the scope of the present newsletter. It is the intention of our Netherlands Sri Lanka Foundation to organize conversations with regards to the subject of ‘slavery’ that would explore new perspectives and complement the ongoing excellent work on the Transatlantic, Asiatic and maybe even other parts of the world like the Middle East ‘slavery’.

In this newsletter we start our conversation on ‘slavery’ in the context of the Dutch East India Company (VOC)’s period of rule in Sri Lanka. We present two items that may be of interest to our readers and could be informative. First I’d like to introduce the item ‘Tracing bonded lives: Stories of enslaved individuals from the archive’ written by Kate Ekama, who is a postdoctoral researcher at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Kate shares her research into the lives of the so called ‘enslaved persons’ in the city of Colombo in Sri Lanka during the VOC period. The second item is authored by Doreen van den Boogaart, our young ambassor, titled ‘A new light on a Sri Lankan made betel box’. She explores the links between the role of one specific artefact – The Betel Box – in the life of the ‘enslaved’. The third item we present is by Georg Frerks, Em. Professor Utrecht University and Netherlands Defense Academy and the chairman of our foundation. Georg has several decades of academic work experience in Sri Lanka. For this newsletter he ventured to undertake an exploratory exercise, based on a limited number of academic and other sources, and discusses the phenomenon ‘slavery’ in Sri Lanka. His contribution is titled “Slavery in Pre-colonial Sri Lanka: What the literature reveals”. In my opinion it sets the stage for the previous two items about ‘slavery’ in Sri Lanka and also future conversations on the subject.

Finally we are pleased to announce that we plan to organize an event that would broaden the scope on ‘slavery’ from purely the historical to the philosophical and religious perspectives as well – precisely because Sri Lanka’s religious diversity makes them so relevant. The objectives would be to improve, or at least problematize, our current understanding of ‘slavery’ from philosophical and ethical angles. Thereby we are also hoping that we can widen these conversations to the more practice oriented themes such as ‘Responsible Business Practices’ and Post 2015 agenda of ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ of the United Nations, and facilitate connections between historical and contemporary manifestation of forced labor. We welcome any ideas and suggestions with regards to these topics. In due course we shall provide more information and an invitation for the event.

Dilip Tambyrajah – Member of Board, Netherlands Sri Lanka Foundation