On display in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam is an object that is inventoried as a betel box. Specific elements on the silver ornamentation on the box point to a workshop in Sri Lanka, mid-eighteenth century. Inside the box are compartments containing the ingredients needed for rolling a betel chewing quid; areca nuts, ginger gum, limestone chalk and betel leaves from the Piper ‘betel’ pepper plant. These leaves are known in Sri Lanka as bulath in Sinhala and vetrilai in Tamil.

During his tour around the island, James Cordiner noted in his A Description of Ceylon, that the habit of chewing this mild stimulant was completely prevalent among the Sinhalese. ‘At all hours and on every occasion the mastication of those articles prevails; and two persons seldom meet without opening their boxes and exchanging a portion of their contents.’ Cordiner also noticed that ‘many of the old Dutch ladies in Ceylon have attained a relish for this practice, which they observe as regularly and enjoy as much as the native.’ From the seventeenth century onwards, also the colonial elite turned to betel chewing, it became primarily a women’s affair.

And this brings us to another story that can be told with the Rijksmuseum betel box. A story one will not usually read about on the museum label. Who the maker, purchaser and owners of this specific box were, is unknown. What is certain however is that betel boxes like this Rijksmuseum box, were at times carried by enslaved girls and women. These servants followed their Eurasian mistresses with all the needed ingredients in a box, so the latter had always their inseparable bulath available. This situation is described by Robert Percival in his The Account of the Island of Ceylon. He also noticed the hostile treatment by their mistresses during social gatherings:

“To these visits they go attended by a number of slave girls, dressed out for the occasion. These girls walk after them carrying their betel-boxes, or are employed in bearing umbrellas over the heads of their mistresses, who seldom wear any head-dress, but have their hair combed closely back and shining with oil. Their chief finery consists in these female attendants, and their splendour is estimated by the number of them which they can afford to keep. These slaves are the comeliest girls that can be procured, and their mistresses in general behave very kindly to them. With that caprice however, which always attends power in the hands of the ignorant and narrow-minded, the Dutch ladies frequently behave in a very cruel and unjust manner to their female attendants, upon very trifling occasions, and in particular on the slightest suspicion of jealousy.”

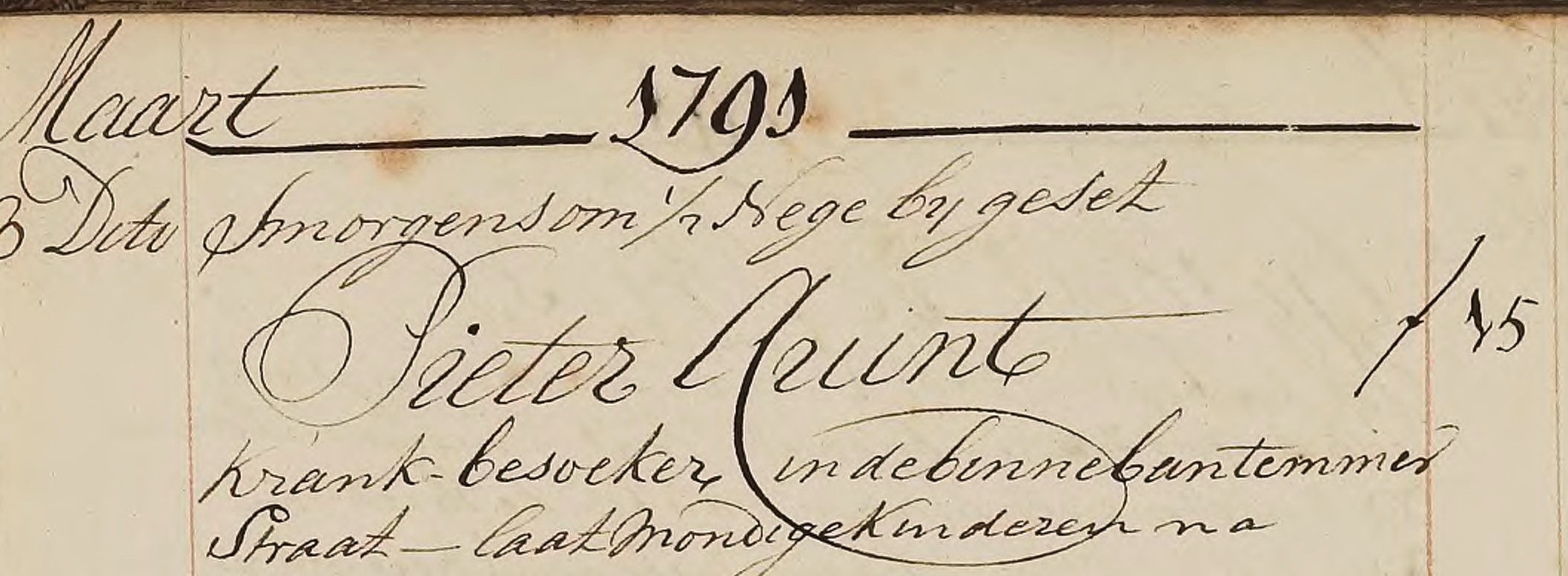

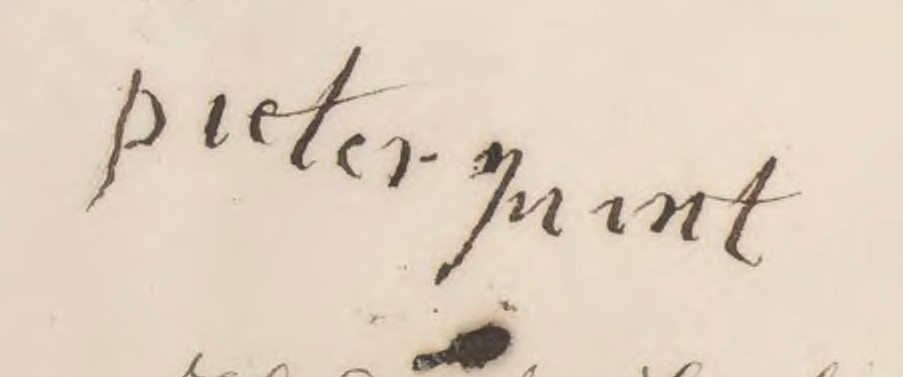

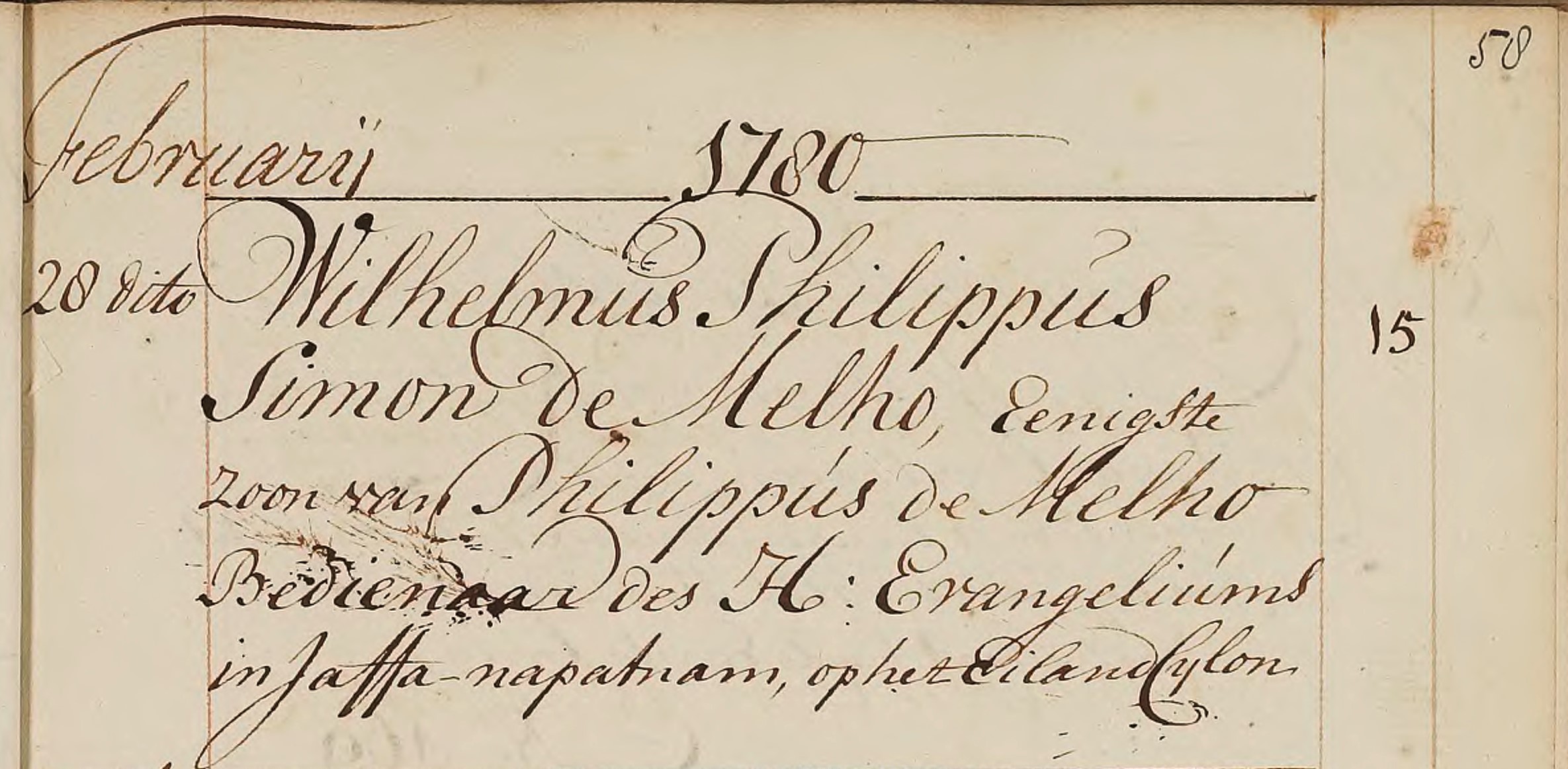

Captured in the Indian Ocean area or born into slavery, these attendants were forced into subordinate positions. In the Dutch colonial records people like them were defined as ‘slaaf’ (slave) or ‘lijfeigen’ (bonds(wo)man). Enslaved persons were often listed as property in personal of governmental documents, like inventories and wills. In the Dutch colonial empire, the colonial powers adopted existing forms of unfree labour, but also introduced a system of lifelong slavery in which people were reduced to a commercial property. Due to this involuntary position, enslaved people could be traded and forced to perform labour.

Enslaved servitude, one of the many forms of slavery, is exemplified on the drawing below. The church-going party displays what was thought to be necessary to bring to church: two enslaved servants, a fan, Bible, betel box and cuspidor. The latter was meant to spit the finished betel roll into. Being seen with enslaved servants was a way the colonial elite showed their wealth and status. On the drawing a man is carrying a payung (parasol) to shield the woman. Carrying a parasol was often a marker of slavery for (young) men in urban colonial Dutch East Indies. Likewise, bearing a beautifully decorated betel box and cuspidor marked the position of (young) enslaved women.

Instead of looking at the exquisite craftmanship of the Sri Lankan made betel box, the attention in this blogpost went to the relationship of this object to colonial slavery. Even though it is not certain if this specific box in the Rijksmuseum was carried by an enslaved servant, it does open up for unfolding the lives of enslaved female servants. However, the colonial archive does not reveal much about them, as the information that the archive contains depended on what the owner or colonial government wanted the world to know. The beliefs, sentiments or experiences of enslaved people were not thought to be important. By using snapshots of their lives from colonial records, but moreover going beyond the written records and engaging rituals, arts, music, oral tradition and also the senses or possible experiences in the reconstruction of the lives of enslaved peoples, their humanity can be retrieved.

In that way, we can wonder if the smell if the ingredients in the betel box remind an enslaved servant of her situation and her freedom that was taken from her. Or did she maybe chew bulath herself, like many enslaved women did? Did it perhaps even feel as an act of protest as she mirrored the one that she had to call mistress? One of her most important tasks was following her mistress and carry her betel box, but for the enslaved woman, a talisman or amulet might have been the most valuable object she was wearing. A reminder of her family tradition or the religion she was secretly adhering. We can think about what social contacts and relationships she was having. We can also try to emphasize with her feelings as she was unjustly threatened. With these kinds of efforts, one refuses to accept the one-sided way enslaved persons were presented in colonial records where their humanity is rejected.

A recent example of this historical project is the exhibition on Slavery in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. The exhibition tells ten true personal stories about people who were enslaved as well as people who kept slaves. Objects that on the first glance do not have a direct connection with the lives of enslaved are used to tell their stories, the exhibition also present sources that have never been displayed in the museum before, like items that were cherished by enslaved individuals or oral histories. The exhibition can be visited online via this link: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/stories/slavery