The first time I visited the beautiful island Lanka, in 2011, I spent many hours in the archive reading about and collecting details of the lives of enslaved people who lived in Colombo when the port city formed an important node in the world of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in the Indian Ocean. I was confronted by the variety of experiences of the enslaved: violence, dislocation, intimacy (chosen and unchosen), death, freedom, inheritance, family life, resistance and loyalty. More than 350 years after the Dutch had conquered the city from the Portuguese, I sat in the archive, poring over the old papers, tracing the lives of many people who have mostly been forgotten over the centuries.

The Dutch East India Company documents which have been preserved offer rich and detailed insights into the experiences of men and women who were enslaved, who lived and worked in coastal areas of the island in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. There are of course many silences and gaps in the archives – at least in part where documents have been lost or not survived the passing of time. The textual sources that still remain range from snapshots of named individuals who appear for instance in the last will of the man or woman who claimed ownership over them, to far more detailed accounts of lived experiences when, for instance, an enslaved man fled from his owner and was on the run for days, which tale he recounted after his recapture.

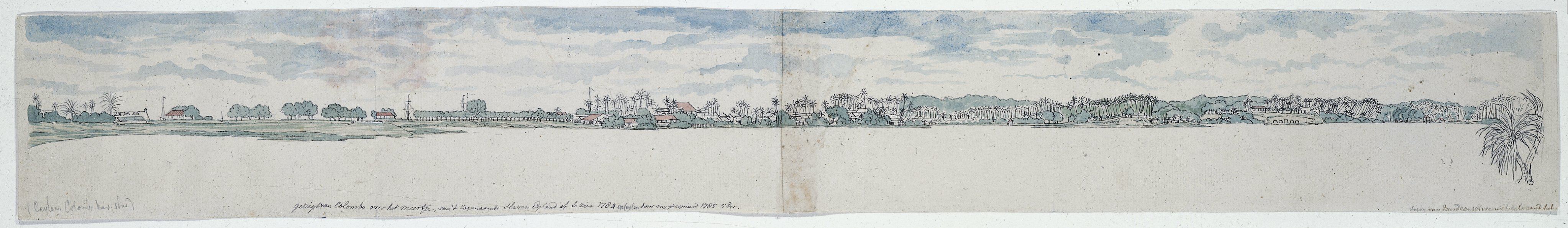

What we can glean from the variety of records is that during the eighteenth century, owning enslaved people was a common occurrence in Colombo. Slave-holdings were not large, certainly not in comparison to plantation slavery in the sugar islands of the West Indies for example, but nevertheless, men and women across the city of a variety of religious and ethnic backgrounds were slave-owners. And the enslaved themselves were from diverse Indian Ocean origins. Based on the way in which they were recorded in Company sources, we can trace at least the place from which they were transported, if not their place of origin. Through names such as Apollo from Makassar, Itam from Goda (Java), Augustus from Cochin, and Modest from Sumbawa we can trace the shipping networks along which routes of forced migration these people travelled (see the map below for most of the locations within the Dutch empire). VOC Ceylon was both a destination for these forced migrants as well as a departure point. Sources from the same period but a very different location – the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa – recount the lives of enslaved people such as Andries of Ceilon who lived and worked on a Cape farm, along with Ceres of Madagascar, a woman named Louisa and her mother, all of whom were owned by the same Cape family.

Through these old documents, we can see that slave-ownership was widespread and we can trace some aspects of individual enslaved people including their names, a guess at their age, and some part of their journey to or from the island. Other sources reveal more details of their everyday lives, and this is especially true of the enslaved men and women who were named in manumission deeds and in court cases.

Manumission was the process whereby an individual enslaved person or a few individuals were declared free. Some enslaved people purchased their own freedom, others were freed on the death of their owner, or as a reward for ‘good and faithful service’. For instance, Kastoerie and her daughter Thomasie purchased their freedom from their owner Manuel Adam Fernando; Breana and her son were manumitted by their mistress Christina van Angelbeek for the ‘exemplary loyalty’ which they had shown.

Over the last few years, a number of scholars have emphasized the need to move away from the binary conception of slavery as the opposite of freedom, a way of conceptualizing slavery that those who study the Indian Ocean world have inherited from the excellent scholarship on the Atlantic but which sits uneasily in Asian contexts, where European colonial empires faced long local genealogies of bonded labour. The intersections and overlaps between forms of bonded labour – including caste and corvée – remain little understood in the histories of slavery in Asia. In exploring the history of slavery in Sri Lanka under the Dutch East India Company, and in particular the sources, it is revealed that the lines between a condition of slavery and living in freedom were certainly blurred. This was true not only in terms of lived experience but also before the law. Through a mid-eighteenth-century court case involving a family and those people who claimed ownership over them, we get some insights into these issues of slavery and freedom, and the spaces between these legal categories which individuals inhabited.

Sabina who lived in Colombo was a mother, a wife and at some points in her life was enslaved. She was also a litigant who spent years in the VOC courts contesting the claim that she was enslaved. The dispute began in dramatic style when a widow barged into a man’s wedding, halting proceedings. The man was Christoffel, Sabina’s son, and the widow claimed to be their owner. The widow’s claim was based on unpaid debts and the case appears to have revolved around whether or not Sabina’s husband, Anthonij, had repaid money borrowed in the past. But what was the connection between his debt and Sabina’s slave status? When Sabina was manumitted she received proof of her freed status, which proof Anthonij used as collateral on a loan. If he could not pay, Sabina and her children would be re-enslaved to cover the outstanding debt. It was Sabina’s freedom and that of her children that was at stake. The resolution of the case has been lost in the intervening years but whatever the outcome of the dispute, it is clear that freedom was precarious, and that even before the law slave and free status were not clear cut.

Over the last few years, since my first trip to Colombo, there have been a number of wonderful books and articles published based on sources including those documents which I pored over in the archive. Most recent among them is Nira Wickramasinghe’s fantastic Slave in a Palanquin. There is of course still much to be done and many lives and experiences of these historical individuals to uncover. Through a variety of academic projects and heritage partnerships, this work is underway.

_______________________________________________________________

Kate Ekama is a postdoctoral researcher at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Her work on slavery in the Indian Ocean focuses on Sri Lanka and the Cape, spanning the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. The work discussed in this post refers to documents housed in the Sri Lanka National Archive in Colombo and to recent published research in the Journal of Social History. You can contact Kate at kateekama@sun.ac.za.