A stroll down the old streets of Colombo’s Fort district would no doubt remind one of the city’s colonial past, with many of its buildings giving out their European descent through their architecture. Amidst this cluster of British and even Dutch heritage buildings and monuments is a small curious monument in the carpark of the Ceylinco House building in the shape of a prison cell. Tradition has it that it once held the last king of Kandy, the last independent native kingdom of Sri Lanka, and indeed so reads the inscriptions on the monument, which is also a protected monument by the Department of Archaeology.

While exploring tidbits of Colombo’s past, my curious mind noticed an inconsistency in this narrative, that academically it was known that the king was not imprisoned here, but placed in a large house and well looked after until his deportation. Then which narrative is true? And then what exactly is this monument? In 2018 I decided to investigate this and produced a research article with a surprising conclusion which I disseminated in online and print media. It turned out that the academic narrative was right and that the present monument was constructed in the 1950s! I attempt here to give a summary of this and take a step further by exploring on a question I ended with in the previously published article; why the conception of such a narrative and monument?

The present monument (Author, 2018)

The popular narrative goes that the king was kept in a cell within the fort of Colombo before his departure, but is it the actual story? In the February 1815 British campaign to oust King Sri Wickrama Rajasingha from the throne; the king who fled the capital was captured on the 18th February 1815 and transferred to Colombo. Arriving in Colombo on the 6th of March the king and his family remained there till the 24th of January 1816 when he was deported to Vellore in South India.

My research showed that according to the Official Government Gazette and the writings of Dr. Henry Marshall, he was kept in a house and placed under house arrest, and not in a cell.

To quote the Gazette No. 704, Wednesday, 15th March 1815:

“On the Monday following Major Hook with the Detachment under his command escorting the late King of Kandy and his family entered the Fort…He is logged in a House in the Fort which has been suitably prepared for his reception and is stockaded round to prevent any intrusion on his privacy”

Dr. Henry Marshall, a contemporary to the event gives a detailed account of the last King, his appearance, his character and a very impartial look at his rise and fall. In his book he states that:

“the prison or house provided for him was spacious, and handsomely fitted up. He was obviously well pleased with his new adobe, and upon entering it, observed, “As I am no longer permitted to be a King, I am thankful for the kindness and attention which have been shown to me”

The writings of Dr. Marshall further confirm beyond doubt, of the king being placed within a house in the fort and not in a prison cell.

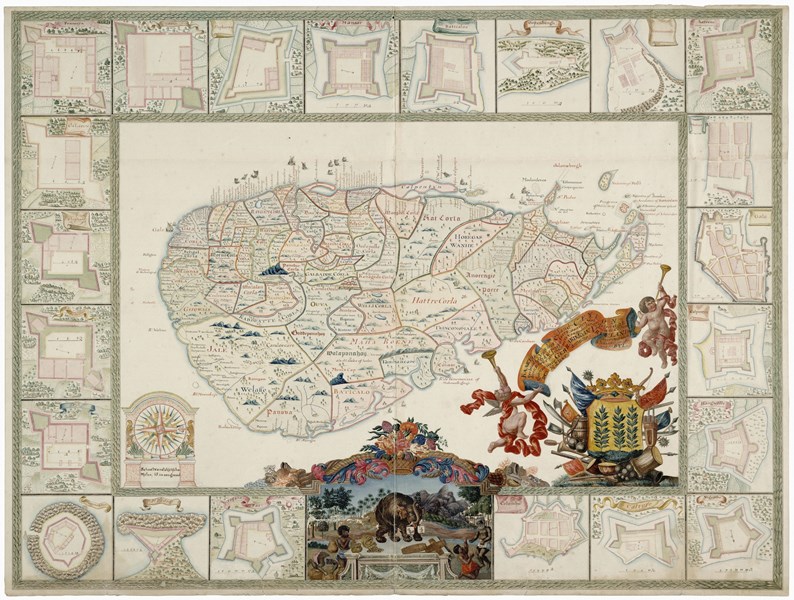

Then where was this house? Here is where the site of the monument and the narrative of the housing of the king comes together. R. L. Brohier states that the king was housed in a Dutch house which was later occupied by the Darley Butler building, and later by the present Ceylinco House – the current site of the monument. My historical survey showed the present location indeed used to be a block of houses during the Dutch period which would have no doubt been there in 1815, just 19 years after the takeover of Colombo by the British.

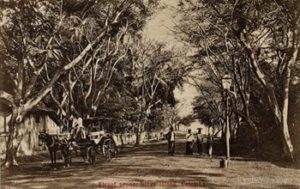

If the king was in a house, then what is this present monument? The Darley Butler building was established on the site of the house prior to 1860 and was later demolished in about 1960 when the Ceylinco House was being built between 1955 and 1962. A significant change to the built landscape around the Darley Butler building occurred in the mid-19th century, where the ramparts of the fort were taken down and a military barracks complex termed the Echelon barracks was built in 1875 – just adjoining the Darley Butler building. A study of a detailed plan of 1904 at the National Archives showed a small box shaped structure just bordering the Darley Butler building to the south which appears to have been a guardroom with an entrance to the barracks facing Queen’s Street. This was confirmed by an old photograph of around the 1920s, which clearly shows the guardroom as square shaped with a tiled roof. Suspecting a relationship between the guardroom and the present monument, further comparative analysis was done with maps and aerial images, which identified the site of this guardroom and the present monument as the same.

Photograph of Queens Street, ca.1920s. RED circle clearly shows the Guard house with entrance (Extract from Sea Ports of India and Ceylon, 2005)

As both the guardroom and the present monument fit to the same location, there appears to have been a modification or complete remodeling made to the guardroom by 1960, as a photograph of that year clearly shows the present monument next to the Darley Butler building together with a still-under-construction Ceylinco House.

Photograph from Baurs building, 1960. RED circle shows the present monument (The Faithful Foreigner, 2015)

Then comes the big question, why? Why create this structure and associate it with the false narrative of the king in a prison? Since its appearance from 1960, it has consistently been associated as a monument of heritage; an authentic prison cell from 1815 where the king was purportedly held. Was this a case of mistaken identity? No. The results clearly showed the narrative of the imprisonment as false and the monument as a reconstruction of a much later guardroom. Hence it could be considered a case of invented heritage; a deliberately ascribed narrative to a ‘new’ structure.

While I wasn’t able to find out why and by whom such a monument was created, it is interesting to explore this question through a socio-ideological lens, not in a sense to find an answer but to explore the possibilities.

Taking an overview of the built heritage of Colombo fort, it is a space of colonial heritage, with built heritage sites from the Dutch period through to the British; however with this present monument being the only indigenous heritage monument in Colombo Fort. If a question is asked of representation in the heritage space, it fits in quite well; it is a monument associated with a Tamil king of a Sinhala kingdom, a representation of the two dominant ethnic cultures of Sri Lanka within the predominantly European space.

If looked at from this perspective of indigenous-colonial representation in heritage space, was this a part of a larger process of decolonization in a post-colonial nationalism-oriented Sri Lanka? Or was it simply a personal whim for a hoax or an adding of extra value to real-estate?

The change from guardroom to prison cell appears to have been made in the late 1950s when the Ceylinco House was being built. This falls within the first decade after independence from the British in 1948, a time of active nationalism and decolonization by indigenizing colonial space. Colombo being the center of colonialism was actively being decolonized; Victoria Park was renamed Viharamahadevi Park in 1958, Queens House renamed to Janadhipathi Mandiraya (Presidents house) and its adjoining Queens Street to Janadhipathi Mawatha, and Gordon Gardens renamed to Republic Square, to name a few. It is therefore tempting to ponder if this ‘prison cell of King Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe’ was a monumental reproduction of the last Kandyan king for a post-colonial Sinhalese identity project amidst colonial European heritage monuments; a form of re-appropriation of heritage space.

Key References:

Brohier, R. L., 1984. Changing Face of Colombo. Colombo: Lake House Investments.

Diessen, R. V., Nelemans, B., 2008. Comprehensive Atlas of the Dutch United East India Company Vol. IV. Cakovec: Zrinksi Printing & Publishing House.

Macmillan, A., Extract from Sea Ports of India and Ceylon, 2005.

Marshall, H., 1846. Ceylon, a general description of the island and its inhabitants. Tisara Prakasakayo (reprint 1969).

Mendis, H.M.C., 2018. Truth behind the Prison cell of the last King in Colombo Fort. Archaeology.lk [online] Available at: Truth behind the Prison cell of the last King in Colombo Fort

Perera, N.,1999. Decolonizing Ceylon: Colonialism, nationalism, and the politics of space in SriLanka. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Ranasinghe, D., The Faithful Foreigner, Thilo Hoffmann, The Man Who Saved Sinharaja, 2015

———————————————————————————————–

Chryshane Mendis

Chryshane is a Sri Lankan graduate student residing in Amsterdam. He has just completed his MA Archaeology in Landscape and Heritage from the University of Amsterdam with a thesis on a GIS inventorying and mapping of Dutch and Kandyan fortifications. He has conducted a comprehensive survey on the archaeological remains of the Fort of Colombo and has since been invited to and delivered lectures to numerous organizations including the Sri Lanka Navy and published both locally and internationally. He is also the author of an upcoming book documenting the history of Colombo’s fortifications which will be published through The National Trust Sri Lanka. His academic interests are on Sinhalese warfare, military history & architecture, military landscape heritage and plans to pursue doctoral studies in Conflict Archaeology. He was also researcher and coordinator of Archaeology.lk through which he has published numerous articles.